One Whistleblower's Story: Losing a job, but not losing hope

/LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT

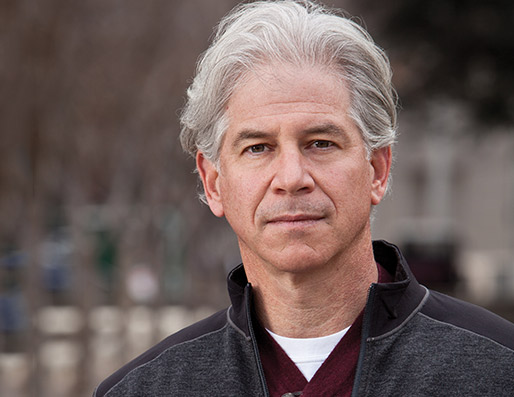

James D. Ratley, CFE

ACFE President

You might eventually have to make a tough decision that could jeopardize your job and disrupt your life.

Let's say you find an accounting regulation violation that your organization might have ignored for years. You bring your concerns to your boss who agrees you've discovered a problem. Other accounting department staff members concur until they figure out the restatement costs. You stew over this and realize that your organization is breaking the law.

You secretly report the violation to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the audit committee of your company's board. Somehow your boss finds out and sends an email to the accounting department's executives. The attorneys review and decide that the company is in compliance. The SEC decides not to investigate the case. You lose your job and your hope.

This is the story of Tony Menendez, CFE. Except he never lost his hope. "In 2005, I was asked to approve a bill-and-hold sale [at Halliburton], and it was at least six years after the SEC issued SAB 101," Menendez says during a recent Fraud Magazine interview. This Staff Accounting Bulletin describes regulations on revenue recognition in financial statements.

He says unassembled equipment wasn't even ready to be shipped to a customer. "Halliburton was holding the equipment in anticipation of performing future oil field services for its customer," he says.

Menendez shared his findings with his bosses, and they initially agreed with him. But they later backpedaled when they realized that correcting the accounting would've required a costly and embarrassing restatement. Menendez went to the SEC, which eventually decided it wouldn't pursue the case. A Halliburton internal investigation cleared the company. Menendez's boss outed him to the company in an email. Halliburton stripped him of many of his duties and banned him from meetings. Colleagues ostracized him. Menendez left Halliburton in 2006 and brought a whistleblower claim under the anti-retaliation provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

In September 2008, an administrative law judge determined that Halliburton hadn't retaliated against Menendez. Menendez then represented himself in appealing the case to the Administrative Review Board (ARB). In September 2011, the ARB overturned the original trial judge. Halliburton appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, but the panel ruled that the company had retaliated against Menendez for blowing the whistle. After almost nine years, he'd won his battle.

"The stigma of whistleblowers hasn't changed nearly enough," Menendez says. "As long as employers see whistleblowers as a rare breed to be feared instead of individuals who add great value to the working team as a whole, it can be hard for them to prevail, and society as a whole bears the greater risk."

The ACFE will award Menendez the 2016 Sentinel Award for "Choosing Truth Over Self" at the 27th Annual ACFE Global Fraud Conference. Read more about Menendez's story in the latest issue of Fraud Magazine.